The Grill

Our challenge was to imagine new ways to address social violence among youth in Boston. During the Studio’s preliminary conversations with youth and youthworkers, we asked what they felt was the cause of the violence they saw around their neighborhoods. One youthworker described it this way: “One guy might be driving through another neighborhood, and he stops at a red light. He sees a guy from that neighborhood grilling him, so he grills back. Then he drives off and goes to get his boys, and it’s on.” In group and individual interviews with over 60 youth, we found an instant, visceral reaction to addressing “the grill” (where two peers catch eyes and assume animosity, often leading to threats or actual violence). Young people thought that shifting this social practice was both impossible and exhilarating.

The grill caught our attention because in our methodology for designing social interventions we look for an entry point, a less explored angle with potential to interrupt social problems. Here was a simple gesture that functioned on a symbolic level to epitomize a system where violence could start over nothing more than “she looked at me wrong”, but also how the nothing was everything, their very reputation and safety being on the line in the instant of response. (Almost all the youth we spoke to said that to not grill back was to be seen as a “punk”, who could then be mistreated by anyone.) So the grill was symbolic, but also a literal act that we could point to, play with and make strange.

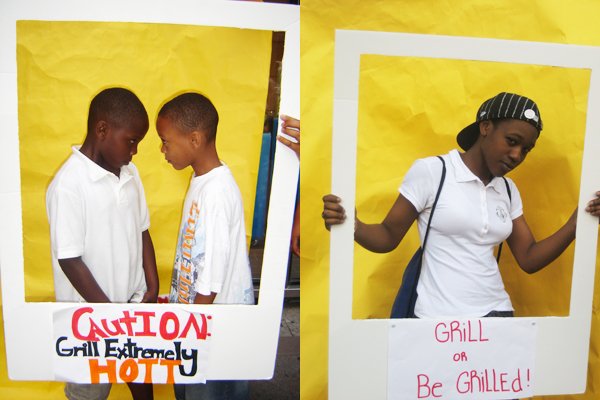

We felt if we could mess with the moment of the grill, we could mess with the power of the grill to demand the grill as response, instantly creating a narrow space of on-edge intensity and aggression. To mess with the moment of the grill, we designed The Polaroid Project. It was done completely in public space, with over 100 young people in Dudley Square, Uphams Corner, Downtown Crossing and at an end-of-the-summer cultural festival hosted by the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative. Our youth interns asked teens and early 20-somethings to give us their “best grill” as they posed holding a “life size Polaroid” frame. We left participants to make their own sense of the point being made, knowing that if it remained a strange experience, it could linger in their minds until the next time they were grilled. At that moment, would they think of the Polaroid? Would they be distracted just enough to cut down on the chance of violence? We, as activists, are used to drilling our point home. Artists have taught us that offering “a moral to the story” actually deflates the power of your intervention.